On July 12, the first full day of the 2011 Province Assembly, Fr. John van den Hengel of the General Council gave two presentations. In the morning he presented the statistics of the congregation, showing how the face of the Priests of the Sacred Heart is changing, and how it will continue to change in the future. Click here to read more about that presentation, and click here to view the PowerPoint slides that went with it.

In the afternoon, Fr. John spoke about Dehonian spirituality. The following is his text from that presentation.

Introduction

In May 2009, just prior to the General Chapter, as a gift from the Canadian Region for my 50th anniversary of profession I went with my brother Bill to Egypt. Our end-goal was a pilgrimage to Mount Sinai. I have had the privilege to teach theology for 40 years at Saint Paul University in Ottawa. What had become more and more central to me – as actually it should for theologians – was the unique way in which God is revealed in the Judeo-Christian tradition. The text of Exodus 3 of the giving of the Name of God and the story of the covenant with Israel has always stimulated my interest and curiosity, particularly when I could let this story interact with the story of Jesus. The Congregation gave me 40 years to do this. For 40 years (give or take a few years) I taught the course on Jesus the Christ. My interest was to create a unified story of the God of Moses and the God of Jesus Christ. More than ever, I have felt, we need to retell the story of God for our time.

It is with this background and curiosity that I was asked to join the General Administration. I have accepted the position with the full intention to give back to the Congregation what it gave me through the 40 years of meditation and reflection on the figure of Jesus Christ and the one he called his Father. I give you this as background to this afternoon’s presentation.

Spirituality: as a priority of the General Administration

A second background note comes from the mandate the General Administration received from the General Chapter: to put Christ at the center. When we began our work we went to Vitorchiano, the South Italian novitiate. We started with adoration and a morning of reflection by ourselves. When we gathered for conversation in the afternoon, we spoke about the spirit with which we would work. We had a lengthy discussion on how we saw our spirituality and the role the Heart of Christ played in it. We wanted our spirituality to be a spirituality, that is, something that pervaded our work. And I think, so it has. We have made it our central priority.

Neustadt, April 2011

- In April of this year the European major superiors held a reflection on our spirituality in Neustadt, Germany. The question we asked of every entity was “Spirituality: what do we have in common as Dehonians?”

- The objective of the meeting was to discern what orientation to our spirituality is being promoted in the various entities. We asked the entities: (1) What do you seek to realize as our spiritual heritage for the young? (2) What is being presented in formation? (3) What is the shape given to Dehonian spirituality in your Province or District? (Slide 67)

From the various responses (all entities responded) it became clear that there is little consensus on the orientation of our spirituality, at least among the Europeans. As a way to explore where the differences lay, we asked all the participants to first of all to choose words and concepts from our tradition, that is, words that are being used in the various entities. Out of the discussion there came ten words or common concepts. Individual groups were asked to discuss five of these: (1) Oblation, (2) Devotion to the Sacred Heart, (3) Eucharist (adoration), (4) reparation and (5) mission. From the discussion two things became clear: (1) that there was a great difference among the Provinces on the understanding of these concepts. In most cases, the words had been re-translated into something else. So, for instance, oblation came to mean for some “disponibility” or “availability”, reparation became reconciliation, devotion became witness, or was said to have lost its power. (2) In every group, it was acknowledged that culturally almost all these concepts were no longer intelligible to ordinary Christians and needed interpretation or the use of other words.

Anyone who has studied these concepts historically as they functioned in 19th century France realizes that the original meaning of most of these concepts has been lost and in each country they have taken on different meanings. Not many today look to the physical heart of Jesus as an object of adoration as was the case in the earliest forms of the devotion. We have made the heart a symbol of love and changed part of the original intent. In the same way we no longer understand “union with Christ” in the same way that Dehon did and certainly not as the French school of spirituality in the 17th century did. So the European superiors at Neustadt touched on something that philosophers in the 20th century have pointed out again and again: all understanding is historical (not relative, but historical). To take a leaf from Paul Ricoeur, a philosopher who has accompanied my life as a teacher, all life is ruled by metaphors. By this he meant that human existence is a constant movement in which semantic resemblances between two semantic fields shape our understanding and our search for truth. Most of human existence does not follow a strict logic. Human existence is most like a narrative with its crises, or changes of direction, which has a narrative logic but not a rational logic. Within most of our lives we have undergone crisis moments. These moments, in hindsight, we can tell and explain – hence the flood of memoirs in our time – but the change of fortune, as Aristotle called these moments, comes from without and not from within.

I believe that for the Congregation such an interaction of two semantic fields, a crisis or change of fortune, took place in the chapter of 1973. In 1973 for us there was an historic clashing of two spiritualities which gave shape to our current spirituality. Here we confronted “modernity” as the Vatican Council had done some 10 years previously. I believe that we have not yet succeeded in reaping the full outcome of this historical event. At the Neustadt meeting, Fr. André Perroux called the chapter of 1973 and the Constitutions that emerged from it a miracle. I tend to agree with him. It is about this that I would like to speak this afternoon. How do we receive Dehon today?

Myth of origin vs. history of origin

I would like to begin by making a distinction in our reception of Dehon. And that is the distinction between the history of our beginning and what, for want of a better term, I will call the myth of origin. It is well known that each human community needs a myth of origin, a story which starts with “in the beginning…” This “in the beginning” does not have to be an historical event. Most “in the beginning” myths point to a time immemorial. They are, like the story of creation in Genesis, a story of the meaning of a group. They talk about a sacred ancestor or a founder. Scripture scholars call these myths an etiological event. A myth explains why things are the way they are. A myth of a founder becomes, as it were, the story of the followers. The followers recognize themselves in the narrative. By telling the story of the beginning, the group or community is given an orientation about what and who they are.

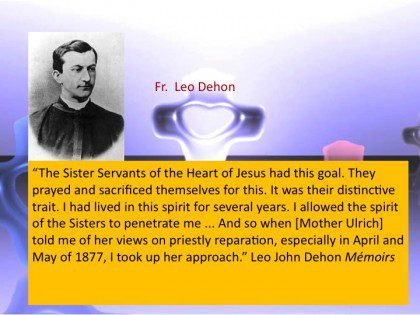

As a Congregation we have a story of our origins, but what I believe is lacking is a myth of origin. We begin our story with Fr. Dehon’s association with the Soeurs Servantes in St. Quentin. Between 1873 and 1877 Leo Dehon was assigned as chaplain to the Soeurs Servantes. They introduced Leo Dehon to a more explicit devotion to the Sacred Heart. It is through Mother Ulrich that in 1877 Fr. Dehon began a Congregation of reparation. With this in mind, Leo Dehon began his year of novitiate. It is tempting to see in this event the myth of our origin.

Historically, it signaled our beginning. Fr. Dehon described it as such in his Mémoirs: “The Sister Servants of the Heart of Jesus had this goal. They prayed and sacrificed themselves for this. It was their distinctive trait. I had lived in this spirit for several years. I allowed the spirit of the Sisters to penetrate me … And so when [Mother Ulrich] told me of her views on priestly reparation, especially in April and May of 1877, I took up her approach.”

However, this story of our beginnings hardly explains the meaning and identity of the Congregation today.

I do not deny that Leo Dehon’s association with the Sister Servants was a significant moment in his spiritual journey. In their common life the sisters had adapted to their circumstances the exercises or practices derived from the manifestation of the Heart of Christ to St. Margaret Mary Alacoque (1647 – 1690). We might be tempted to take this story of our beginnings as the myth of our origin because Leo Dehon seemed to have done so. When he wrote his first Constitutions in 1877 and 1885 he seemed to draw the meaning and purpose of the Congregation from the Sisters. From them he took the mass and communion of reparation, the acts of oblation, the celebration of the first Fridays of the month, adoration and holy hour. By all accounts the story of the beginning became the founding myth. But is this so?

Deconstructing the story of our beginning as a myth of origin

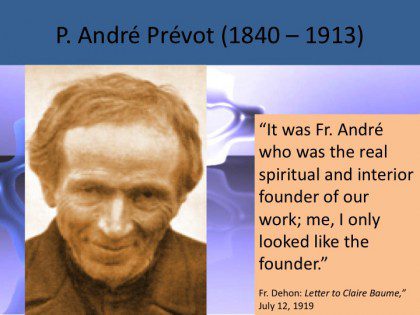

From the beginning there has been a sense that the meaning of the Congregation is not totally bound up with the Soeurs Servantes. From the beginning, there was also an awareness of a difference between the victimal spirituality of André Prévot and Leo Dehon’s spirituality. From his writings, but particularly his actions, it quickly became obvious that Dehon’s own faith experience was broader than both these trends. Dehon’s own spirit also pushed him – as we know – beyond the private devotion of individuals to a social engagement of the devotion to the Sacred Heart. We know of internal tensions in the Congregation because of this in the chapters of 1893 and 1896. Fr. Dehon may have ceded publicly to the spirituality of André Prévot and given him the responsibility to form his earliest followers, but Fr. Dehon’s own spirituality did not feel bound to or limited to Prévot’s.

Interpretative key

The most decisive break in the interpretation of our story of origin actually does not come from any particular story of Dehon’s life. It is to be found in XVI General Chapter of 1973. Here the story of our origin was deconstructed as our myth of origin. For most of the participants – and I was one of them – the outcome was clearly experienced as a break in the reception of the tradition of the Congregation. Its offspring: the Rule of Life of 1986 orients us towards a different myth of origin, but does not clearly indicate it. There are no references to it. The only reference to the Soeurs Servantes and St. Margaret Mary are found in the retention, in Latin, of the first two chapters of the 1956 Constitutions. These two chapters did not become part of the Rule of Life proper. It delinked the Congregation’s spirituality from St. Margaret Mary and the Soeurs Servantes.

It seems to me that what we have begun in the chapters of renewal of 1973, 1979 and 1985 has not really been brought to its logical conclusion. We have not, as a Congregation, clarified what binds us. We have not as yet succeeded as a Congregation to implement the aggiornamento of the underlying intuition of the Rule of Life. My experience in the General Administration in the last two years has shown me how useful it would be to have greater consensus. The Neustadt meeting of the European major superiors in April showed how important such a discussion of our spirituality is.

The dilemma

Perfecta Caritatis and Ecclesiae sanctae after Vatican II insisted that religious communities needed to start their renewal from the charism of the founder. This charism, it was held, gave the impulse to the Congregation. When the church accepted the Rule of Life, it confirmed that we had found and articulated this charism of the founder. So when the new General Council in 2009 wanted to start its program of actions, it had to make a decision about our point of departure. That point would be the great spiritual insight of Fr. Dehon; we had to use it to give shape to our work. After some deliberation, the Council chose to start with the intuition of the Rule of Life. It is in the intuition of the Rule of Life that we must seek the myth of origin to lie in the faith experience of Fr. Dehon.

The faith experience of Fr. Dehon

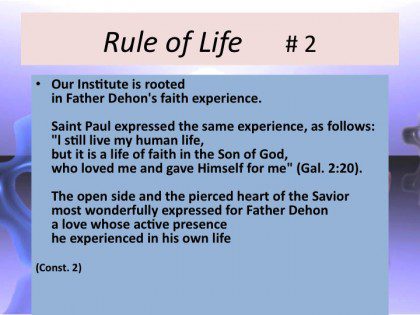

In number 2 of the Rule of Life we read:

Our Institute is rooted

in Father Dehon’s faith experience.

Saint Paul expressed the same experience, as follows:

“l still live my human life,

but it is a life of faith in the Son of God,

who loved me and gave Himself for me” (Gal. 2:20).

The open side and the pierced heart of the Savior

most wonderfully expressed for Father Dehon

a love whose active presence

he experienced in his own life.

What we have in this number of the Rule of Life is a first attempt to arrive at a myth of origin. When it was first articulated, it was an intuition. However, the intuition was accepted and confirmed in subsequent chapters. However, as a Congregation we have never fully appropriated this and reflected on its consequences. I think Albert Bourgeois was well aware of the importance of this intuition. He wrote a three-volume interpretation on the new Rule of Life in which he defended the authenticity of the insight of the Chapter (Studia Dehoniana 15). Although the Rule of Life was well accepted in the Congregation, in some way, its influence on our thinking and living was only peripheral. What was described as our spirituality never became our founding myth. Only lately has Fr. André Perroux sought to test the intuition of the XVI General Chapter and allowed us to come closer to what stirred the soul of Fr. Dehon. We have a ways to go.

Allow me one viable example of where we might look. In his reading of Fr. Dehon’s many writings, Fr. André Perroux was struck by the many scriptural quotes found in these writings. He decided to compile a list. Up to this point he has found more than 19,000. From this abundance slowly another image of Dehon emerges: Leo Dehon as an indefatigable reader of the scriptures. It becomes apparent that Dehon himself was not so attached to the imagery of the Sacred Heart that he found all his inspiration there. He was never satisfied. All his life Leo Dehon was a searcher for God in the Word of God. And what becomes clear as well is that he sought to understand himself before this Word of God. The deeper identity of Fr. Dehon – and hence a myth of origin for the Congregation – ought to be sought in his meditatio and oratio of the scriptures.

What did Fr. Dehon seek? What emerges more and more from the study of these numerous quotes is his search for the heart of God. He understood this core, this heart, of God to be love and he obviously wished to be grasped by it. That is why at first Fr. Dehon took hold of the devotion of the Sacred Heart from the Soeurs Servantes. It allowed him to acknowledge this heart of God. But he soon found this view too narrow. Within a decade he was expanding this spirituality of the Heart of God beyond individual souls to include also the soul of society. However also this focus was still too narrow.

Fr. Dehon’s spiritual quest was more like a journey of discovery of what was for him the originating force of life, not only of individuals but also of society and creation. It took him a life-time of searching. By recognizing his life-long reading and meditation of the scriptures in search for the heart of God as the spiritual quest of Dehon, we may be closer to his soul. His was a life-long prayer and contemplation of the heart of God. Because Fr. Dehon recognized that this was really at the heart also of the devotion to the Sacred Heart, he could bind this contemplation of the love of God to the practices of the devotion to the Sacred Heart. But outside of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries these practices may no longer be adequate. We thereby acknowledge the creative hermeneutics of the XVI General Chapter in its daring reshaping of the myth of origin of the Congregation.

Leo Dehon could not, in his time, untie the spirituality of the Sacred Heart from the devotion. That began to happen with the liturgy of the Sacred Heart and also in the encyclical Haurietis aquas. Both the liturgy of the Sacred Heart and the encyclical on the Sacred Heart, Haurietis aquas, broke with the centrality of St. Margaret Mary for the interpretation of the Sacred Heart. As # 96 of the encyclical of Pius XII in 1957, Haurietis aquas, says, “It must not be said that this devotion has taken its origin from some private revelation of God and has suddenly appeared in the Church.” Or as another number in the encyclical says, “There are some who, confus[e] and confound the primary nature of this devotion with various individual forms of piety which the Church approves and encourages but does not command…” (# 10) The Congregation did not follow suit. For us it took the creative hermeneutics of the XVI General Chapter to do so. It asked us to seek the “memoria” of Fr. Dehon beyond one or other historical event, beyond Margaret Mary, beyond the Soeurs Servantes and Mère Véronique. It asked us to look for our inspiration in a deeper layer of his personality: the impact of his experience of the love of God on his life and activity. Perroux is right. We need to look for Dehon’s mystical roots (or mystico-political roots).

Among the many quotes, the text found in # 2 of the Rule of Life, was clearly a favourite. In his study, « Le Fils de Dieu m’a aimé, il s’est livré pour moi. Galates 2, 19-20», Fr. André Perroux wrote down all the texts in which Fr. Dehon quotes Galatians 2.19-20 and provides a brief commentary.[1] He arrived at a 110 places where Fr. Dehon refers in one manner or another to the Pauline experience of faith in the love of God. It turns out to be Fr. Dehon’s most quoted text. In a subtitle of this article he asks: “How did Fr. Dehon read this text of St. Paul? How can this reading, in the context of the Church today, contribute to an understanding of our “spirituality”?”[2] Although not the only “revealing” text, Galatians 2.19-20 is the one Fr. Dehon must have experienced as coming closest to his God experience. The Rule of Life acknowledges with the same breath, however, that the resemblance of Paul’s experience of God to Fr. Dehon’s is not exclusive. There are other sources. Cst. 2 also points to the account of the open side and pierced heart of Christ.

Although the scriptural quote in # 2 of the Rule of Life is a core example of Fr. Dehon’s orienting faith experience, it does not say it all. It needs to be broadened. As every myth of origin it can never be enclosed in a “final” interpretation. It cannot be closed because what it seeks to express cannot be encamped. That is also intent of the various mottos of the Congregation: Ecce venio, Sint unum and Adveniat regnum tuum. All reach to a beyond that is measured in faith and hope but cannot be captured in a singular event or a particular action.

For brevity sake let us therefore briefly examine what we can learn from # 2 of the Rule of Life. We recognize there three guidelines to our spirituality:

1. Like so many other founders, Leo Dehon had an experience of Christ. It was not a sudden event because Dehon’s relation to Christ dates from his early childhood. We have no conversion story or a unique mystical experience. Dehon’s journey of faith was life-long. From his intense reading of the scriptures, we uncover a Dehon who at all times was circling around a deep inner experience of Christ. We see it as the task of the Congregation at this time, to search out this experience and bring it to life within the Congregation. It is probably also the reason why more than ever the Lectio divina ought to be encouraged as a central spiritual practice in the Congregation. In this context # 2 intuited that Dehon’s faith experience of Christ resembled that of Paul’s conversion or call narrative in the Letter to the Galatians. Our Rule of Life quotes only Chapter 2, verse 20: “l still live my human life, but it is a life of faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave Himself for me” (Gal. 2:20). The “life of faith in the Son of God” of Paul includes his experience of being “crucified with Christ” and of Christ living in him. For Paul the experience of the love of God revealed in the cross, of a God who would self-annihilate for us, gave him the faith, his trust and confidence, in God’s love. Fr. Dehon sought a symbol of God’s love for him and he found it similarly in God’s self-abandonment, in God’s oblation, God’s self-gift, revealed in Christ. He found the symbol of this oblation in the heart of Christ. It was this experience that Fr. Dehon sought to make his own. This scriptural experience is foundational for us. This is the image of Christ that underlies our spirituality.

2. A second guideline for our spirituality is the emphasis in # 2 of the Rule of Life on the faith experience of Fr. Dehon. The experience of Christ in his pierced side is an experience of faith. As an intense reader of the scriptures, Fr. Dehon wanted not only to meditate and pray the scriptures but also to read his own life through the scriptures. His search for God was at the same time a search for himself: to know himself in the mirror of the scriptures. This exercise of searching the scriptures to reconfigure his inner self stands as model for us. It is important to note here that what is primary is the personal experience of being loved.

If Paul’s experience of faith is our point of reference, this faith experience of Dehon is to be interpreted as an experience that convinced him about something in Jesus. For Paul it meant that he needed to be convinced that Jesus was a stronger motive for adherence to God than the law had been. Paul needed to be convinced by God that a right relationship with God did not lay in the keeping of the Torah, the law, but in faith in Jesus. It was the cross of Jesus that finally convinced Paul of the love of God for him. That was his faith experience, his conversion experience. In line with this we may also see in Fr. Dehon, in his constant quoting of Galatians 2.19-20, a search for the reassurance of God’s love for him. Fr. Dehon’s spiritual quest was more like a journey of discovery of what was for him the originating force of life, not only of individuals but also of society and creation. Paul found reassurance in the cross. It gave him faith. Dehon found assurance in the Heart of Christ. For him the devotion to the Sacred Heart was an expression, a symbol, not the origin, of his experience. It was the proof of God’s love. That is why the devotion as expressed by the Soeur Servantes is not as central as was thought in the first century of the existence of the Congregation. Fr. Dehon scoured the scriptures and was fed by the much larger story of God’s desire for us.

3. Finally there is also a third point in the Rule of Life that brings this charism full term. That is where this faith experience of Christ becomes our faith experience. In the past this meant to engage in the practices of the devotion. During my recent visit to Poland all the practices of the devotion to the Sacred Heart which I learned so well during my novitiate in Ste. Marie were still intact, singing of the Litany of the Sacred Heart every day during the month of June. From the devotion most of us have retained the adoration and the act of oblation, the first Friday of the month and the solemn celebration of the Feast of the Sacred Heart. Some of the other practices we have dropped. On their own they may seem to us to keep alive our bond with the Congregation. We often use them as identity markers, of how we pass on the spirituality of the Heart of Christ in our parishes and how we live it in communities. As Haurietis aquas indicated, our relation to the heart of Christ as the heart of God does not have to pass through some of the practices attached historically to the devotion. But obviously some of them do.

What remains central for us is the Eucharist: the celebration of the self-gift at the heart of Godself. Attached to the Eucharist, we hold on to adoration. But only when we do not lose sight that adoration in its connection with Eucharist is the continuing self-gift at the heart of Trinity. We have tended to objectify what we have called transubstantiation into an objective presence, an object to be worshipped instead of the symbol of God’s constant self-agency in our midst. (But don’t get me going on this topic!)

To these practices the Congregation has been adding in recent chapters and documents the practice of Lectio divina. It seems to us that in a time when faith is endangered and God has become more a mystery again, we need to do what Dehon did: that is, to search out in the scriptures the language and the symbols of God. What attracts us to Fr. Dehon, more than ever, is this life-long search for a personal experience of the love of God. The language of the bible is for us the language of God’s revelation. What better way in our time than to attach ourselves to its wealth to feed our personal thirst for God. That is why the General Administration has been advocating the practice of Lectio Divina as a central practice for bringing alive the charism of our founder.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this re-reading of our charism has certain other benefits that will become more important as the Congregation goes south (!). This view of our myth of origin could allow us to incorporate different practices, also different cultural influences than the ones we have known thus far. It would free the Cameroonians and the Indians from having to assume the French background of so much of the Sacred Heart devotion and of the spirituality of Fr. Dehon. It would, in the future, open up the possibility of a new cross-fertilization of our spirituality once it has gone through the inculturation process of new peoples. On our part, we can begin to more fully follow Fr. Dehon’s example in that he found what his heart was searching for in an incessant reading and meditation of the scriptures.

I think it is not far from the mark to recognize our ground in this intense, spiritual search of our Founder for the heart of the Father in the love of Christ and to see in this search the myth of origin of the Congregation. Although the scriptural quote in # 2 of the Rule of Life is a core example of Fr. Dehon’s orienting faith experience, it does not say it all. It needs to be broadened. As every myth of origin it can never be enclosed in a “final” interpretation. It cannot be closed because what it seeks cannot be encamped. Fr. Dehon’s reach into the love of God, as is ours, is a never-ending search into the ineffable.

[1] To my knowledge this text of 59 pages has not been published.

[2] See also John van den Hengel, Faith in the One Who Loves Me (Ottawa, Milwaukee: Priests of the Sacred Heart, 2007)