January 9, 2015

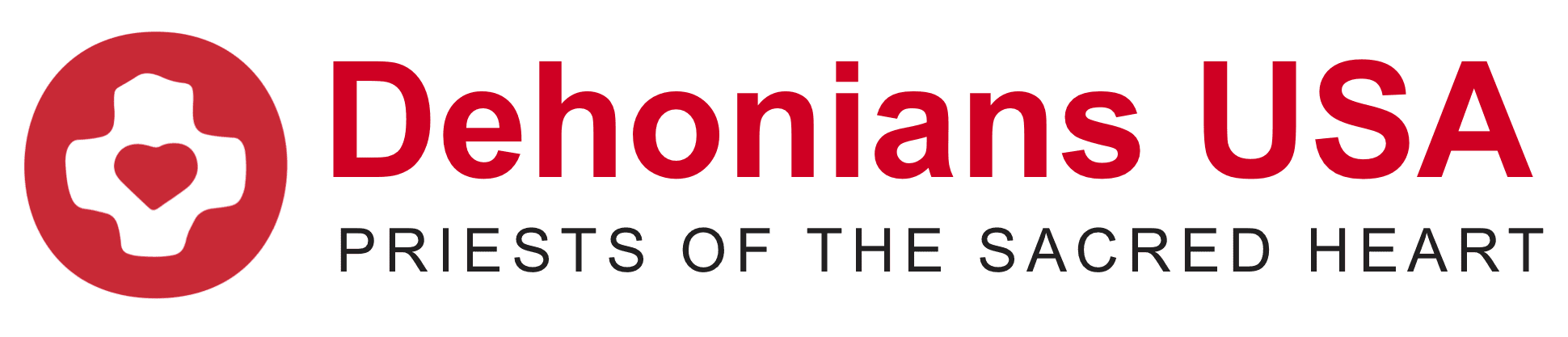

The most striking feature of this image of the Heart of Jesus seems to be the energy or movement of the figure; this Heart of Jesus is not serene. His backward-streaming hair and the folds of his clothing suggest that Jesus is walking at a brisk pace. Also notable is his gaze, which is not fixed on the viewer, but directed beyond, perhaps inviting the viewer to observe what he sees. His pierced left hand draws attention to his Heart that is surrounded by emanating rays. The human heart pumps blood throughout the body; the Heart of Jesus sends accepting, forgiving, and transforming love throughout the universe. His pierced right hand is lifted high in a gesture at once witnessing to his presence in the world and rallying his followers to action.

The most striking feature of this image of the Heart of Jesus seems to be the energy or movement of the figure; this Heart of Jesus is not serene. His backward-streaming hair and the folds of his clothing suggest that Jesus is walking at a brisk pace. Also notable is his gaze, which is not fixed on the viewer, but directed beyond, perhaps inviting the viewer to observe what he sees. His pierced left hand draws attention to his Heart that is surrounded by emanating rays. The human heart pumps blood throughout the body; the Heart of Jesus sends accepting, forgiving, and transforming love throughout the universe. His pierced right hand is lifted high in a gesture at once witnessing to his presence in the world and rallying his followers to action.

This image challenges those who reflect upon it to understand grace—another word for God’s love—as the energy needed to bring about conversion, whether individual or societal. Grace is not something to be measured or stored, but rather an energy to be expended. Love is less a sentimental feeling than a consuming fire or overflowing fountain.

Followers of the Heart of Jesus are an active bunch. They open themselves as wide as possible to take in a portion of God’s grace, set their faces resolutely toward whatever reality is in front of them, and lovingly do their part to bring about needed change. Their focus might be on their own prejudice, fear of aging, or consumerism; it might be on homelessness, militarization, or global warming. And while conversion is usually incremental, each step widens the capacity to take in God’s grace, act from the motivation of God’s love, and bring about the Reign of God.

November 14, 2014

“What immense depth has the ocean! What breadth! What profundity! One tries sometimes to take a sounding of certain parts, but what we know of it, what we have been able to explore, is a mere nothing! And the Heart of Jesus is like that too. The litanies call it, The depth of all virtues, Receptacle of justice and love, Plentitude of all graces, Source of life and holiness, Source of all consolation.

“But what are the means to extract these treasures that are in the Heart of Jesus? All one needs for this is a little good will and a few minutes of reflection and prayer. One must apply oneself to understand the sentiments of this divine Heart, to penetrate their nature in a short meditation. After which one must humbly acknowledge the imperfection of our interior life and of our affections, when faced with the sentiments and affections of the Heart of Jesus.

“Abyss! Immensity! How we are impressed by the ocean, when one can no longer see anything of the continent! Where are the limits of this abyss? How far do these liquid masses extend? What is their depth? Our Lord, speaking to Margaret Mary, liked to compare his Heart to the ocean. ‘Come in this abyss of my Heart,’ he said to her, ‘and seek the limits of my love, you will never find them.’ How I would like to throw myself into the ocean of the mercy of the Heart of Jesus, in the abyss of his virtues and his graces!”

In the Heart of Jesus, Fr. Dehon contemplates an abyss of humility, patience, zeal, and self-sacrifice. With the gift of the Eucharist, he reflects on the Heart of Jesus as an abyss of love. “No one can have greater love than to lay down his life for his friends [John 15:13]. The abyss of friendship is to give his life again and again, every day, although without the shedding of blood; it is to remain always there, close to one’s friend.”

Directly addressing Jesus in this meditation, Fr. Dehon writes, “You speak according to the dispositions of those who come to you. You consent to a touching and sometimes intoxicating heart-to-heart. But there is an abyss of love far deeper than these encounters, and that is communion. Yes, you penetrate our breast because you want to be very close to our heart; because you wish to impassion our whole being, all our senses, to purify everything, sanctify everything, make everything divine.

“What an abyss of charity! Then you stay within us through a spiritual presence. He who eats my body and who drinks my blood, remains in me and I in him [John 6:56]. You said that there is no greater love than to give one’s life for those whom one loves. You forgot to say that the abyss of love is to give oneself in communion to those whom one loves.”

Fr. Leo John Dehon, SCJ, from a series of meditations entitled, Lessons of the Sea.

October 17, 2014

The motto of the Visitation Order, of which Margaret Mary Alacoque was a member, is, “To be extraordinary by being ordinary.” It has to be a Trickster God who chose Margaret Mary to receive visions of Jesus and revelations from his Sacred Heart asking for a loving response to God’s unconditional love. In making her visions known, she was not quite living up to her Order’s motto, raising many suspicions about her, not only in her day, but also in ours.

She saw Jesus’ five wounds shining like bright suns and heard these words: “Behold this Heart which has loved humanity so much and that finds only indifference, neglect, and ingratitude among most people—and often even among those whom it has honored with a special love.” These words began an Act of Reparation that the Priests of the Sacred Heart prayed daily before the renewal of Vatican II.

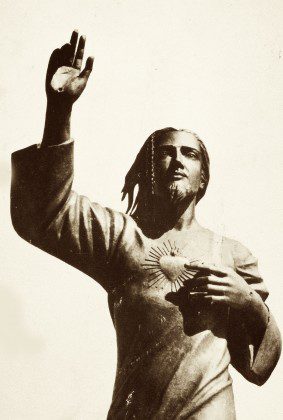

The mandala displays five concentric suns. The warm colors and the color placement give the mandala a vibrancy, which exudes much energy. The mandala’s border consists of the repetition of the words, “extraordinary” and “ordinary.” Like a koan, these words invite the viewer into paradox in order to meditate on its wisdom.

The sun is an ordinary part of life, but as the essential element of life, it is extraordinary. It may be taken for granted, but is nonetheless the source of life and energy for Earth and its people. With all the wounding and woundedness in the world, Jesus’ wounds could seem quite ordinary. His, however, look like suns—sources of life, energy, and warmth—very extraordinary. In the context of devotion to the Heart of Jesus, these wounds symbolize God’s unconditional love.

Humanly speaking, the experience of being wounded often encourages people to respond by wounding others. That’s a very ordinary response. Yet, making a return of love honors wounds as a reminder not to wound others. Indeed, wounds can teach how to love others deeply, gently, and compassionately. That is extraordinary.

The lived spirituality of devotion to the Heart of Jesus is as essential as the life-giving energy of the sun—at once both ordinary and extraordinary.

September 26, 2014

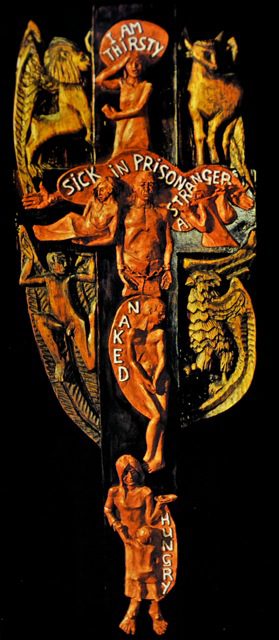

Catholics favor the image of a crucifix—the body of Jesus hanging on a cross. On this cross, however, hangs the mystical Body of Christ experiencing the pressing need for food, drink, inclusion, dignity, health, and freedom. Jesus identified these needs and identified with these needs in his description of the final judgment [Matthew 25:31-46]. Jesus’ physical body, visible only by his hands and feet nailed to the cross, merges as one with his mystical body.

Symbols of the four Evangelists flank the crucifix. The traditional image of Mark as a lion, Luke as an ox, John as an eagle, and Matthew as a human, are appropriated from the four living creatures, with multiple sets of wings, attending the throne of God [Ezekiel 1:5-12, Revelation 4:6-8]. The Gospel writers stand as witness to the experience of Jesus and his ministry of solidarity.

Most people in Jesus’ day barely had the means to maintain their life. Hunger was always gnawing and no doubt Jesus occasionally felt it himself. From his compassion, Jesus feeds a multitude [John 6:1-14]. To the mother on the cross, who has little to offer her hungry child, Jesus declares, “I am the bread of life” [John 6:35].

In an arid climate, water was a precious commodity. Jesus, dehydrated and exhausted from the tortures of crucifixion, cries out, “I thirst” [John 19:28]. To the woman on the cross, who with a gesture of desperation holds an empty cup, Jesus promises, “Those who drink of the water that I will give them will never be thirsty” [John 4:13-14, 7:37-38].

As an itinerant preacher, Jesus had “no place to lay his head” [Matthew 8:20] and many rejected him [Luke 17:25]. To the stranger on the cross, carrying a sack of few possessions, Jesus tells the parable of the Good Samaritan, which challenges Christians to be a neighbor to anyone in need [Luke 10: 29-37].

Immediately after Pilate passes the death sentence, guards strip Jesus of his clothes and mock him with caricatures of royal insignia [Matthew 27:27-31]. At his crucifixion, the guards throw dice for his clothes [Matthew 27:35]. To the man on the cross, exposed to the elements, trying to cover himself, and looking away in embarrassment, Jesus echoes the prodigal father, solicitous of his returning son, “Quickly, bring out a robe—the best one—and put it on him” [Luke 15:22].

As Jesus traveled the countryside with large crowds following, his fame as a healer spread beyond Israel’s boundaries. People brought to him all who were afflicted with various diseases and Jesus cured them [Matthew 4:23-25]. To the invalid on the cross, who is confined to his bed, Jesus willingly says, “I will come and cure you” [cf. Matthew 8:7].

Abusing his power as a petty ruler, Herod imprisoned John the Baptizer, and this had ramifications for Jesus’ ministry [Matthew 4:12]. To the shackled man on the cross, Jesus says, “The Spirit of God has sent me to release captives” [Luke 4:18].

This crucifix reminds us that we are the mystical Body of Christ. What we do or fail to do for our sisters and brothers, we do to ourselves and we do to Christ. Jesus calls us to be his hands and feet. Jesus calls us to be his heart—generous to all who turn to him.

September 5, 2014

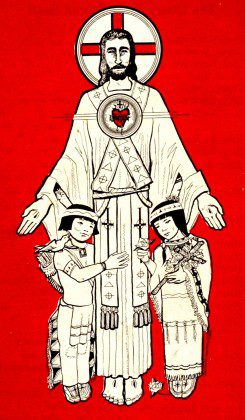

“How often,” Jesus laments over the city of Jerusalem, “have I desired to gather your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you were not willing!” [Luke13:34]. No doubt, Jesus’ heartfelt desire is mindful of the psalmist, who, in the shadow of God’s wings, sings for joy [Psalm 63:7] and desires to take refuge [Psalm 17:8, 36:7, 57:1]. In the image to the right, two Native American children, and by extension, all God’s children, willingly gather under the arms of the Heart of Jesus, who blesses and protects them as they move into the promise of the future.

Wearing traditional Lakota dress, the boy and girl represent an abiding respect for nature and faith. The girl holds a cross, fashioned from branches and adorned with flowers, as she contemplates the beauty of a single blossom. The boy, with a bird singing on his shoulder, carries a quiver filled with arrows, suggesting the Native Americans’ sacred dependence on their animal relatives for sustenance. His arms hug Jesus’ leg in a gesture of familiarity and comfort.

The halo encircling Jesus’ head and heart suggest his divinity, while his delighted facial features suggest his humanity. Jesus wears a stole, a priestly vestment decorated in repeating geometric patterns reminiscent of the quill and beadwork of the Plains Indians. The wounds of his passion speak of his complete self-offering for the benefit of the human race. His pierced hands, feet, and heart embody the Lakota prayer, “O Wakan-Tanka, be merciful to me that my people may live.”

In Jesus’ day, the proud citizens of Jerusalem rejected his attempts to lead them closer to God. However, those who humble themselves like these children, invite Jesus to take them in his arms, lay his hands on them, and bless them [cf. Mark 10:13-16].

August 22, 2014

The Priests of the Sacred Heart want to educate “from the heart,” from their spirituality. As the new, Christian faith community flowed from Jesus’ pierced and opened heart, so does a new, well-grounded generation sprout from the opened and giving hearts of Dehonian educators. As fertile soil in which to plant seeds and let them germinate, the heart nurtures but does not constrict the developing shoots, leaves, and fruit of the new plant.

The Latin word, educare, hopes to communicate to the international congregation of the Priests of the Sacred Heart that education entails more than instruction or training. The holistic development of every young person requires educators to share their time, attention, and affection. To educate in this way is a form of living life abundantly as Jesus promised [John 10:10].

The Latin word, educare, hopes to communicate to the international congregation of the Priests of the Sacred Heart that education entails more than instruction or training. The holistic development of every young person requires educators to share their time, attention, and affection. To educate in this way is a form of living life abundantly as Jesus promised [John 10:10].

The motto, Sint unum, is one of the Dehonian attitudes valued in a school run by the Priests of the Sacred Heart. These words come from Jesus’ prayer to his Father on the night before he was executed. Jesus prayed that his disciples throughout the centuries might be so completely one that their union would witness clearly his message of love to the world [John 17:11, 20-23].

Dehonian educators collaborate in a single project within the congregation. As brothers and sisters, their differences enrich one another and their unity witnesses to an interconnected world. They unite their hearts to the Heart of Jesus for the continual growth of humanity.

August 15, 2014

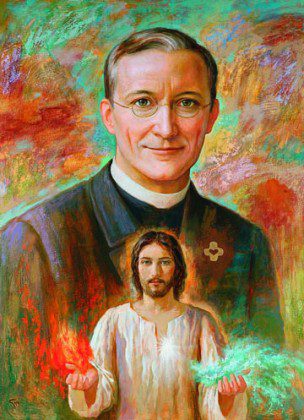

Energy seems to be the most striking feature of this painting commissioned by the Spanish Province of the Priests of the Sacred Heart and created by Goyo Dominguez. The youthful look of Fr. Dehon and Jesus, their gaze directed at the viewer, the burst of light emanating from Jesus’ heart, and the splash of blood and water from Jesus’ outstretched hands filling the entire background communicate a contagious dynamism.

The blood and water allude to the final moments of the crucifixion scene in the Gospel of John. Immediately after Jesus exclaims, “It is finished” and gives up his spirit, a soldier pierces Jesus’ side, from which flows blood and water [John 19:30-34]. Symbolically, it is the Church which flows from the completion of Jesus’ work on earth. Receiving, participating in, and sharing the life and energy of Jesus is another way to speak of the sacraments of Baptism and Eucharist. The placement of this image of Jesus directly in front of Dehon’s heart visually suggests that this expression of the Heart of Jesus nourished Fr. Dehon’s interior life.

Indeed, it is in union with the Heart of Jesus that Fr. Dehon wished to embrace reality. Using the Latin translation of “It is finished,” Dehon spoke his own Consummatum est at the moment Rome suppressed his five-year old Congregation of Oblates of the Heart of Jesus. Although he firmly believed that “the Work,” as Dehon referred to his religious community, had been God’s will, he obediently accepted the painful decision. Yet, in the unfathomable workings of Providence, from what seemed like complete destruction, flowed the restored Congregation under the name “Priests of the Heart of Jesus.”

With their earthly work now finished, both Jesus and Dehon present the viewer with blood and water. Born from this life and energy, followers of Jesus and members of the Dehonian family are challenged to carry on the work of proclaiming the reign of God and making it a reality in a world that often privileges the few to the detriment of many. Yet, even from setbacks, failures, and seeming ineffectiveness, flows abundant life and transforming energy that proves to be contagious.

Note: One image can have different meanings. This is not the artist’s interpretation. Click here for an explanation [in Spanish] of the artist’s Trinitarian interpretation as an expression of Dehonian spirituality.

August 1, 2014

“Meet at the heart.” Whether it was a Visiting Sunday, a Saturday hike, a communal recitation of the Rosary, a ride into town, or even a punishment detail, the place to meet was at the driveway turn-around in front of the main building of Divine Heart Seminary, a boarding high school in Donaldson, Indiana. The cultivation of the triangular plot of land at the end of a long, tree-lined driveway took various forms, from a simple garden of rocks and monochromatic flowers outlining the shape of a heart to an ambitious blooming reproduction of the logo of the Priests of the Sacred Heart.

As a visual focal point, “the heart” indicated a place at the center of things, around which many activities revolved—welcomes, good-byes, and rendezvous. As a quiet sentinel, “the heart” also symbolized the core from which every activity took meaning—the unconditional love that God has for people and the Christian challenge to reflect that love in the daily grind of limitations, disappointments, comparisons, and competition.

The image of the Heart of Jesus points not only to the essence of God, but also to the essence of humanity. Embracing this reality, however, requires the constant spiritual practice to “meet at the heart”—the heart of God, the heart of the individual, the heart of the matter—in order to remember one’s true identity and continue growing into, as our Creator intended, an image and likeness of God.

JULY 11, 2014

Heart of Jesus, broken for our sins.

Heart of Jesus, broken for our sins.

“Surely he has borne our infirmities and carried our diseases,” the prophet Isaiah proclaims as he contemplates the life of God’s faithful servant. “He was wounded for our transgressions, crushed for our iniquities. He poured out himself to death and was numbered with transgressors; yet he bore the sin of many, and made intercession for the transgressors” [Isaiah 53:4, 5, 12].

“Crucifixion Today,” a sculpture by Herman Falke, a Priest of the Sacred Heart from Canada, offers a haunting image of the crush of sin. Jesus’ drooping hands, head, and lifeless body seem to be weighed down by screaming headlines. “Chaos, terrorism, cancer, killers, cruel, deadly, and dangerous” cover the body of Jesus and the cross on which he hangs. The reality of the human condition is as stark as the black and white newspaper.

Out of an immense love, Jesus was willing to be broken for our sins—not broken down, but broken open—making intercession for transgressors, halting the vicious cycle of retaliation, offering the possibility of abundant life, and drawing to himself followers who will do the same.

May the daily news challenge us to do what we can to relieve the heavy crush of sin, even if we are wounded in the process. United with the Eucharistic Heart of Jesus, may our bodies be broken open and poured out to nourish a starving world with a banquet of love.

Herman Falke, SCJ, “Crucifixion Today,” mixed media

JUNE 27, 2014

Heart of Jesus, house of God and gate of heaven, have mercy on us.

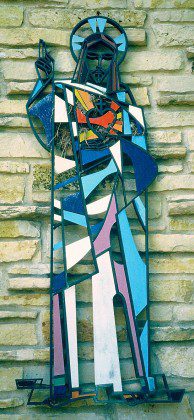

A unique image of the Heart of Jesus greets residents and guests of Sacred Heart Seminary and School of Theology. With the look of stained glass, but constructed with colored sheets of metal, this figure is mounted on an outside wall close to the main entrance.

The intended iconography is traditional—Jesus’ left hand holds his heart surmounted by a cross, and his right hand, held up with two fingers raised, indicates his human and divine natures. The unintended iconography is the addition of a nest that birds build every year behind Jesus’ heart.

“House of God and gate of heaven,” an invocation from the Litany of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, echoes Jacob’s exclamation upon waking from a dream in which he saw angels descending and ascending on a stairway between earth and heaven, and in which he heard God promise companionship and protection. “Surely, the Lord is in this place—and I did not know it,” Jacob responds, adding with a sense of fear, “This is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven” [Genesis 28:10-17].

Perhaps what frightened Jacob was the sense of intimacy. “This place,” which seemed quite ordinary to Jacob, not only linked earth and heaven, but also occasioned Jacob’s consciousness of God’s presence standing “beside him.” So, did God’s presence sanctify the place or sanctify Jacob? Did God intend to dwell in the holy site at Bethel or dwell with Jacob himself?

The outdoor image of the Heart of Jesus raises a similarly intriguing question. Do birds build a nest in Jesus’ Heart or does Jesus make his home in the bird’s nest? The Psalmist prays, “How lovely is your dwelling place, O Lord of hosts! Even the sparrow finds a home, and the swallow a nest for herself, where she may lay her young, at your altars, O Lord of hosts, my King and my God” [Psalm 84:1,3]. Yet, the Letter to the Ephesians insists, “You are members of the household of God…In Christ Jesus, you are built together spiritually into a dwelling place for God” [Ephesians 2:19-22].

Either way, to be one with the Heart of Jesus is to be at home with oneself and with the world.

JUNE 6, 2014

Heart of Jesus, king and center of all hearts, have mercy on us.

This invocation, from the Litany of the Sacred Heart, describes a facet of the multi-layered symbolism of Jesus’ heart. Although Jesus taught extensively about the reign of God, he never directly identified himself as king. He did, however, claim to be shepherd, a role closely identified with Jewish kingship from the time of the Shepherd-King David.

A shepherd tends to the welfare of his flock, not from a distance, but in its midst. As the Good Shepherd, Jesus willingly lays down his life for his sheep [John 10:11-18]. Alluding to his passion, death, and resurrection, Jesus predicts, “When I am lifted up from the earth, I will draw all people to myself” [John 12:32]. Jesus is the heart or center of the flock.

Yet, he also dwells in the heart or center of each individual where “there is no longer Greek and Jew, but Christ is all and in all” [Colossians 3:1-11]. St. John Eudes teaches, “Not only does Christ belong to you, but he also wishes to be in you, living and reigning in you. He wants whatever is in him to live and reign in you: his spirit in your spirit; his heart in your heart, all the faculties and senses of his soul and body in those of your soul and body.”

The image to the right is a detail of the crucifix that hung in the chapel of Divine Heart Seminary. The crucified Jesus, usually stripped of his clothing, instead wears priestly vestments. As a priest, he makes an offering to God the Father on our behalf. As a shepherd, whose heart is with his flock, he himself is the offering. Jesus is a king who reigns from the cross, gently urging his flock to emulate him in spirit, heart, mind, and body. His peaceful face assures us that our self-offering, lovingly united to his, is the dawning of the reign of God among all people.

MAY 30, 2014

For while we were still weak, at the right time, Christ died for the ungodly. Indeed, rarely will anyone die for a righteous person—though perhaps for a good person someone might actually dare to die. But God proves his love for us in that while we still were sinners Christ died for us. Romans 5:6-8

Just as I am, without one plea, / But that Thy blood was shed for me,

And that thou bidd’st me come to Thee, / O Lamb of God, I come! I come!

Just as I am, and waiting not, / To rid my soul of one dark blot,

To Thee whose blood can cleanse each spot, / O Lamb of God, I come! I come!

Just as I am, tho’ tossed about / With many a conflict, many a doubt,

Fightings and fears within, without, / O Lamb of God, I come! I come!

Just as I am—poor, wretched, blind; / Sight, riches, healing of the mind,

Yea, all I need in Thee to find, / O Lamb of God, I come! I come!

Just as I am—thou wilt receive, / Wilt welcome, pardon, cleanse, relieve,

Because Thy promise I believe, / O Lamb of God, I come! I Come!

Just As I Am

Text: Charlotte Elliott, 1789-1871; Tune: William Bradbury, 1816-1868

MAY 9, 2014

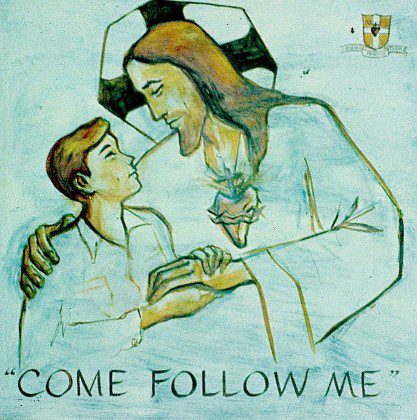

Three times a day, approximately 200 high school seminarians sat in the presence of this large painting of the Heart of Jesus that hung in the Divine Heart Seminary dining room. Most likely, it took only a few meals before the constantly hungry crowd completely blocked out the image from its consciousness. Yet, no other image of the Heart of Jesus managed to be so personal for this group of teenagers.

Although the message seems straightforward, the image suggests what the words, “Come, follow me” involve. The boy looks up to Jesus, as he would to a hero or mentor. Jesus returns his gaze. The traditional image of Jesus’ heart—with cross, crown of thorns, and flames—highlights the call to follow with a love passionate enough to be inclusive, strong enough to overcome obstacles, and faithful enough to endure the cross. By resting his right hand on the boy’s shoulder, Jesus affirms his vocation and awaits his response. Using both of his hands to clasp Jesus’ other hand, the boy willingly commits himself to this collaboration of love and service.

Just beyond Jesus’ shoulder, the boy is able to see the traditional emblem of the Priests of the Sacred Heart, which reproduces the image of the heart with cross, thorns, and flames. Although there are many ways to follow Jesus, he has received a call to join this particular religious Congregation. Most of the young men who attended Divine Heart Seminary eventually discerned other vocations, but this image impressed upon them that every call is a personal encounter with Jesus and deserves a loving response.

APRIL 18 2014

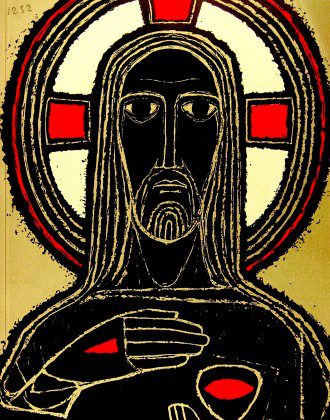

A somber image of the Heart of Jesus, rendering minimal detail in black and white with red highlights, may not at first glance seem appealing. Indeed, most people need time to assimilate a hauntingly challenging depiction of unconditional love. No matter your first reaction, take a few moments to gaze upon the image to the right.

Perhaps the most striking feature of this image is Jesus’ eyes—wide open and looking directly at the viewer, as if waiting for a response. The red wounds on Jesus’ body echo the red cross suggested in the halo. Jesus’s bodily wounds and cross signify, for those of us who are Christian, his willingness to prove God’s love for us “while we were still sinners.”

His left hand cups his heart, reminding the believer that what is essential is not suffering, but rather the love by which any act is undertaken for the sake of others. Jesus holds his right hand just below his throat as if his wounded hand speaks without words of the depth of love that flows from his total offering of self.

This unsentimental image of the Heart of Jesus seems to ask, “Do you understand what is important here?” and “Are you willing to follow my example?”

unsentimen

APRIL 18 2014

Heart of Jesus, patient and rich in mercy.

A boy about 10 years old was playing ball in the park with an adult, who appeared to be his grandmother. Standing a short distance from each other, the woman kicked the ball to her grandson. If her aim was slightly inaccurate, he watched the ball roll past him. Slowly, he would go after it, and with some encouragement, kicked the ball back.

How pained this woman must have felt to see her grandson so incapable of responding in a way that most boys do. It was evident, however, that she did not think spending this time in the park with her grandson was wasted. She continued to kick the ball to him and encouraged him to kick it back to her. Although difficult to discern what he experienced, her inexhaustible love for him, as he is, seemed certain.

This sad and loving scene epitomizes an invocation from the Litany of the Sacred Heart.

Given the circumstances of life, this grandmother is, like the Heart of Jesus, “patient and rich in mercy.” In Fr. Dehon’s thought, she is ready to do God’s will by responding to all that Divine Providence asks of her. Her life is a book, and what is written there is her love.

love.

APRIL 11 2014that t

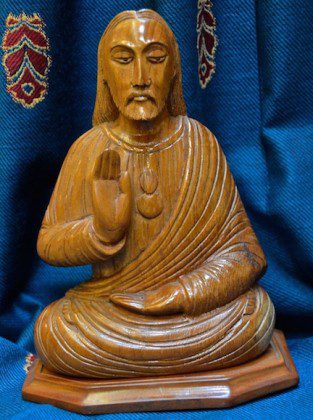

Images of the Heart of Jesus abound, but only a few seem to hold the attention of most Catholics. Yet, the variety of images proves helpful to those who understand that their spirituality is nourished, not only with affirmation, but also with challenge. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then unconventional images of the Heart of Jesus can serve to awaken a new consciousness, expand understanding, and deepen faith.

To a Westerner, it might seem strange to see an image of the Heart of Jesus in a meditative pose favored by the contemplative traditions of Hindus, Buddhists, and Jains. Yet, it’s possible that most Catholics in India, being in the religious minority, would be equally surprised to imagine Jesus looking different from the Western portrayals that are almost universal throughout Christianity.

In this image, Jesus is sitting in a cross-legged or lotus position, which supports meditation by encouraging proper breathing and bodily alignment. His eyes remain open, but focused downward. His left hand, resting on his lap, depicts a traditional gesture of meditation, while the open palm of his right hand, raised at chest level and facing outward, indicates fearlessness, spiritual power, and a blessing of deep inner peace. Jesus is simultaneously meditating and sharing the benefits of his prayer.

The pose is one of a guru or teacher, so highly revered in the culture of India. With a simple outline of the heart on his chest, this image calls to mind Jesus’ words to his disciples. “Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble of heart, and you will find rest for your souls” [Mathew 11:28-29].

What does this image teach you about the connection between your prayer and your daily activities? What does this image suggest about religious expressions that are not your own? What specific expression of God’s love does this image of the Heart of Jesus suggest to you?

MARCH 28, 2014

Images of the Heart of Jesus abound, but only a few seem to hold the attention of most Catholics. Yet, the variety of images proves helpful to those who understand that their spirituality is nourished, not only with affirmation, but also with challenge. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then unconventional images of the Heart of Jesus can serve to awaken a new consciousness, expand understanding, and deepen faith.

Take a moment to gaze upon the image to the right. Unique features include Jesus’ inclined head, his dark complexion, and the use of light to emphasize his serene face and large heart. What do these features suggest to you?

A possible way of interpreting this image comes from a talk that Fr. Leo John Dehon presented at an Ecclesiastical Congress in 1895, reflecting on the Church, “as the common mother of the rich and poor.” Although he was working with an image of St. Yves, his description mirrors this image of the Heart of Jesus.

“It is said that in a stained glass window in a church in Brittany, the good St. Yves is depicted standing larger than life, between a rich person and a poor person whom he has the mission of bringing together and reconciling; but his head is inclined and his expression directed visibly toward the poor person. Is that not the Church’s role? She loves all her children, but she has a preference for the small and the weak. She is democratic. In the sphere of social economy, let us be democrats like Pope Leo XIII, by protecting the interests of the weak and by re-establishing, particularly in their favor, the reign of justice and charity.”

As seen from the lens of Fr. Dehon’s social consciousness, what do you sense this image is saying to you? In what way might this image awaken within you a new consciousness, expand your understanding, or deepen your faith?

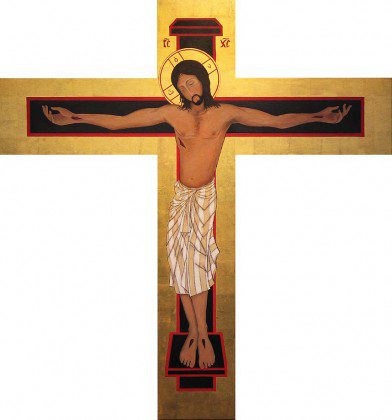

MARCH 14, 2014

Fr. Charles Brown, SCJ, who created the image of the crucified Christ, seen at right, explains that it is a visual presentation of an early Christian hymn, which St. Paul quotes in his letter to the Philippians (2:6-11). It attempts, largely without words, to express layers of meaning, including a classic reading of the hymn, and another, perhaps original one.

The classic reading is centered on Christ. This text describes how the sinless Son of God, united from all eternity in triune Godhead with the Father and the Spirit, debased himself and poured out his life on the cross for the salvation of humankind. The concluding verses then express the fact of Christ’s risen glory.

The classic reading is centered on Christ. This text describes how the sinless Son of God, united from all eternity in triune Godhead with the Father and the Spirit, debased himself and poured out his life on the cross for the salvation of humankind. The concluding verses then express the fact of Christ’s risen glory.

Another, perhaps original, reading is centered on humankind and is an ancient Christian commentary on Genesis, chapters 1-3, with Christ as the lens. The first humans, created in the image and likeness of God, exploited that likeness through their disobedience (notice, the serpent tells the woman, “you will be like God”).

In their disobedience, the first humans brought sin and death into God’s good creation. In his self-emptying on the cross, Christ, in the form of God, refused to grasp or exploit his divine likeness (as the first humans did), and by his refusal he overturned the power of sin and death in creation. Because of Christ’s self-offering, his risen exaltation becomes a foretaste of human transformation. Christ’s triumph tells us who we are becoming.

So, we find at least two layers of meaning in Philippians 2:6-11. Both ways speak of Christ Jesus: one from the divine perspective and the other from the human. These intersect in Christ himself who, through his death and exaltation, has restored to humanity the promise of being in God’s image.

If you choose to use this image as a focus for your prayer, it may be helpful to note several of its visual markers and to consider the affirmation and challenge it contains. Jesus’ five wounds, but particularly his opened heart, are the clearest expression of Christ’s self-offering. Christ’s physicality and the demeaning cross are framed in gold and scarlet, conveying exultation and transformation. The Greek abbreviations at the top of the cross, indicating “Jesus Christ,” and the Greek phrase around Christ’s head, meaning, “the one who is” (Exodus 3:14), are expressions of “the name that is above every name” given by God.