Founder’s Day

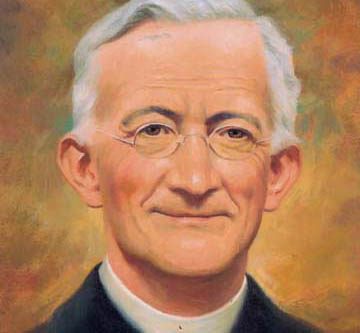

March 14 marks the 170th anniversary of the birth of founder of the Priests of the Sacred Heart, Fr. Leo John Dehon, Born in 1843 to a French aristocratic family, he credited his mother for his devotion to the Sacred Heart, a devotion which inspired him found a religious community focused on bringing people to the love of the Sacred Heart and to promoting a more just society for workers and the most disenfranchised.

The anniversary of his birthday is known in the congregation as “Founder’s Day;” a day that celebrates the vocation of religious life as a Priest of the Sacred Heart.

What follows is a letter from Fr. José Ornelas Carvalho, superior general commemorating the day.

PRAYER VIGIL: Click here to download a prayer vigil for the day.

Dear Confreres,

One of the most frequently quoted texts of our Rule of Life, paragraph 7 expresses the expectation of Fr. Dehon that his religious be “prophets of love and servants of reconciliation.” This year, in writing the letter to the Congregation on the occasion of the birthday of Fr. Dehon, we want to recall this great vocation of the Congregation. March 14 is our Dehonian Vocation Day. It is a day that we recall our vocation but also the reason why we invite others to join us as a community. We invite others because we are convinced of the necessity to continue the ministry of love and reconciliation in the Church and the world.

Accompanying this introductory letter on our vocation is a fictional letter of Father Dehon to the Congregation on the topic of this year. In it the writer reminds us that although Fr. Dehon does not use the word reconciliation, there is a constant theme in his writings of what he calls redamatio, a return of love for love: “Let us place all our confidence in his love and let us give him our love in return.” (NQT 1, 99) These words invite us to see reconciliation in the light of the gift of love that we have received.

Part of our mission is to invite others to join us in the prayer and action of reconciliation. We do this with the awareness that we wish to be part of a work not begun by us but by the mercy of God. More than ever is this the gift of the gospel for our time. Those of us who live in the northern countries have found how difficult it has become to hear this gospel. There is a great hesitation and uncertainty, especially among young people, to accept it as a gift also for them. In the past few decades, because of the numbing influence of secularity upon religious consciousness, but also because of the waves of abuse scandals, religious life and a commitment solely to the kingdom of God has little attraction. This situation makes the vocational ministry to be particularly difficult. We can only rejoice when we hear that in some countries, confreres have turned to innovative ways to make contact with the young and not so young. Those of us who live in the southern hemisphere, although rejoicing in the number of young people who express a desire for the religious life, are very much aware of the challenges, also for them, which the modern, global, secular circumstances of life have put in their way. In celebrating the memory of the birth and life of Fr. Dehon this day, we acknowledge the work of the people working in the vocational ministry who play such an important role in keeping his memory alive among us.

We also acknowledge on this day the life and spiritual vitality of those lay people who have found in Fr. Dehon an inspiration for their lives. In this past year, the General Administration took an initiative to allow more lay people to enter into the spirituality of Fr. Dehon. A small group of Dehonians have begun to put together a spiritual path which will help those who wish to get to know Fr. Dehon and our spirituality to find a way in. We hope to complete a first version of this work in the next year.

March 14th this year falls in the midst of the Lenten period. For Christians reconciliation is inextricably connected with the narrative of the death and resurrection of Christ. The difficulty of breaking down the walls that humans have created around themselves to protect them against the other becomes magnified for us in the story of the exclusion, condemnation, and death of Jesus. He was made sin for us: he became the excluded one. At the heart of reconciliation and the human conversion lies, therefore, the suffering and death of Jesus. The freedom and life that Jesus bought passed through his death to burst forth as the power of the Holy Spirit upon the world in what we call his resurrection. That is why the resurrection stories are filled with greetings of peace and the power of forgiveness. It is the broken and raised body of Christ – symbolized in his pierced side – that gathered the despairing, fearful and dejected disciples into a new community. The memory of violence – the wounds in the hands and feet and side of Jesus – remains as a mark carried on the body of the risen one. It is the crucified Christ who is with and in God. The violence of the world is brought into the healing presence of God. The cross remains the symbol of the possible transformation of humanity into a reconciled community.

This is the vocation we are privileged to live and which we invite others to share. We wish you a great day of remembering Fr. Dehon and his ministry of reconciliation as it is continued in his family.

In the Heart of Christ,

José Ornelas Carvalho

A letter from Fr. Dehon…

As Fr. General notes in his letter above, the following is a fictional letter of Father Dehon. In it the writer reminds us that although Fr. Dehon does not use the word reconciliation, there is a constant theme in his writings of what he calls redamatio, a return of love for love: “Let us place all our confidence in his love and let us give him our love in return.” These words invite us to see reconciliation in the light of the gift of love that we have received.

14 March 2013

My Dear Sons,

I was delighted to receive the request to address you on this annual occasion, but I must admit that my joy was mixed with surprise. It is not as if I had failed to leave you without ample testimony of my vision and aspirations for our common life. Indeed, one of my biographers has aptly remarked that my published writings are like a vast forest where one would hesitate to enter for fear of getting lost.[i] Nevertheless I have no hesitation in responding to you. Ever since my days as a seminarian in Rome I have been convinced of the wisdom of Augustine’s teaching that no one should be so contemplative that in his contemplation he does not think of his neighbor’s need; nor should he be so active that he does not seek God in contemplation (NHV VI, 54).[ii] Even in heaven we fulfill the twofold commandment of love of God and love of neighbor. Of course, it goes without saying that I shall not lift the veil beyond which I have joined Jesus, our forerunner, who has become our high priest forever according to the order of Melchizedek (Hb 6:19-20).

But then I was doubly surprised when I learned that you wanted me to write on the theme of Reconciliation. As you well know, “reconciliation” was not a subject that received a great deal of attention during my lifetime. In Abbé Bergier’s Dictionnaire de Théologie, which was a standard reference book at that time, under the heading Réconciliation it said: See Rédemption. And as best I can recall, even Father Franzelin, my most learned — and saintly — professor of theology, only touched on “reconciliation” in passing. Even in my “vast forest” of writings, of course I cited the key passages in Paul’s letters where he refers to it, but I never specifically developed his teachings in great detail. Instead, in my writings, particularly my meditations, I focused on what the classical spiritual authors referred to as “the mysteries of the life of Christ:” his incarnation and birth, his teachings and miracles, and his passion, death, and resurrection, especially as he continues his risen life among us in the Eucharist.

Paul, on the other hand, did not know Jesus of Galilee, and his own letters predate the written gospels. So, not surprisingly, he shows little interest in the earthly Jesus prior to his passion, death, and resurrection. Rather than focus on the details of Jesus’ life, Paul is more concerned with what he accomplished: the enduring effects of his “work.” He uses a series of about a dozen words to denote the various aspects of this “work,” among which the most significant are: justification, redemption, salvation, and reconciliation. Over time, redemption and salvation have functioned as generic terms for the whole work of Christ. Nevertheless each of these many images or metaphors expresses a distinctive aspect of the mystery of Christ and his work; no single one of them — nor even all of them together — would be adequate to express the full significance of Christ’s “work.”[iii] For as the evangelist assures us, if all that Jesus said and did were written down, “the whole world could not contain the books that would be written” (Jn 21:25). Deus semper maior.

Saint Paul’s teaching on redemption/salvation is obviously not fully contained in the idea of reconciliation. But the consequences of sin not only reduced humanity to a miserable condition, it also resulted in a separation from God.[iv] Thus among all the terms that he uses, it is only “reconciliation” that draws attention to the interpersonal aspect of Christ’s work on our behalf. This is how the word was already understood in both Jewish and Hellenistic culture. For example, the man who was bringing his gift to the altar should “go first and be reconciled with his brother” before he can worthily offer his gift to God (Mt 5: 23-24). And the woman who is at odds with her husband “must either remain single or become reconciled” with him (1 Cor 7:11).

In his Letter to the Romans Paul seems to make reconciliation the ultimate goal and purpose of justification: “Therefore, since we have been justified by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ” (Rom 5:1). Here he is affirming that justification, namely, not holding our trespasses against us (2 Cor 5:19), is the means that allows us to attain something else: it gives us access to peace and friendship with God. (As Saint Thomas said: “Reconciliation is nothing other than the repair of a friendship.”[v]) Then Paul goes on to add that “if, while we were enemies, we were reconciled to God through the death of his Son, how much more, once reconciled, will we be saved by his life” (Rom 5:10). In this instance, reconciliation is the decisive step on the way to salvation. In other words, now that we are no longer enemies, but reconciled thanks to the death of Christ, we are assured of being saved by the Risen One who lives new life.[vi] Friendship with him means sharing in his new risen life. Thus reconciliation is central and plays a pivotal role in Christ’s “work” on our behalf. It is the result of our being justified in Christ, and it is the decisive invitation (2 Cor 5:20) — the gift, the grace — that gives us access to the way of salvation.[vii]

Like most of my contemporaries I did not make Paul’s teaching on reconciliation the explicit focus of my studies or spiritual life. As a seminarian in Rome I kept a “spiritual diary” in which I barely mentioned the Sacred Heart and never employed the conventional phrase “love and reparation.” Instead, I often made use of the terms redamare/redamatio: the return of love for love. “’While we were still enemies, God sent his only-begotten Son’ (Rom 5:10) . . . Let us return love for love” (NQT I, 6-7). “Let us place all our confidence in his love and let us give him our love in return” (NQT I, 99). The theological meaning of “reparation” is not derived etymologically from its Latin homonym reparare, “to repair,” rather semantically, in terms of its meaning, it is derived from redamare, which means “to return love for love.” Just as Scripture never says that God is reconciled to sinful humanity, likewise God is never the passive subject of reparation: sinful humanity does not repair its relationship with God.[viii] Without realizing it at the time, the term that I was using — redamatio — simultaneously comprised both the spirituality of the Sacred Heart and the Pauline understanding of reconciliation with God. “Even in your glory, Lord, you are preoccupied with our salvation . . . How could our hearts not respond to yours? Loving us so much, who would not return love for love [redamaret]?” (NQT II, 40). Initially, I was prevented from seeing this connection because of another assumption that I had made without being fully aware of its consequences.

Reconciliation is not exactly the same as forgiveness. I can forgive someone who does not ask me to, but it takes two to be reconciled. Reconciliation between persons is reciprocal, whether the grievances are mutual or not. However, there is one form of reconciliation that is not properly bilateral: i.e., when the party who has not given any real cause for the separation has always remained faithful in his love and kindness to the other party, and has not stopped wanting a return and reunion (this is true of the father of the Prodigal Son).[ix] The reconciliation of someone with God is a unique case, thus the terms borrowed from common human experience are always inadequate to express it. It is true that God’s reconciling love is always objectively offered, and each individual must freely, subjectively, accept it and appropriate it to himself. But when understood in these terms there is always the danger that it will lead to an intimiste spirituality of “Jesus and me,” which neglects the social, interpersonal dimension of fellowship with Christ.

Although I believe that I never fully succumbed to this trap, it always lurked in the shadows of the hothouse environment of school and seminary. It was not until I was assigned to the parish in Saint Quentin, where I was in daily contact with the working poor and their families, that this threat of self-absorption quickly and permanently dissipated. The objective-subjective image of reconciliation was replaced by a more dynamic vertical-horizontal understanding of reconciliation[x] as the embodiment — the incarnation — of the twofold commandment where the love of God led me to my neighbors, who, in turn, reflected back the suffering face of the Ecce homo (Jn 19:5).

I am sure that you are already familiar with my ministry as a parish priest in Saint Quentin, a city of 30,000 people, most of whom were nominally Catholic. Those who did not attend Mass regularly (the majority!) rarely saw a priest. Long before Pope Leo XIII issued his call “Go To the People” I heard this as my personal call. I initiated several new ministries — a youth club, another for young workers, a third for a committee of patrons. By means of these and other social works I was attempting to bring the “Work” of Christ into their lives. Twenty years later I was active on a diocesan and regional level, organizing conferences on various social issues. I was convinced that as priests and Religious we needed to be informed about economics, business, and the law, but first and foremost we were to be heralds of Gospel, bringing justice and reconciliation to the workplace. On the opening page of my first book on the social question I set forth the values of this Christ-centered vision of society:

“Every person has inalienable dignity, duties, and rights. Whatever social class one belongs to, every person is endowed not only with a living body, but with an intelligent, free, and immortal soul which God created. Having come from God, this soul should serve God and return to God. Whether this soul lives in the body of a worker at the bottom of a dark coal mine, or in the body of a well-fed financier living in the lap of luxury, it doesn’t matter: in reality, both of them have the same value. They have equal personal dignity, equal moral responsibility, the same eternal destiny, and both of them have been given earthly existence so that through truth, morality, and religion they may strive for eternal life” (OSC II, 3).

I realized, of course, that social inequality and injustice were intractable problems. “The poor you will always have with you” (Mt 26:11). But like the craftsmen who spent a lifetime constructing a medieval cathedral and never saw its completion, we too must work to contribute what we can to make it all a little bit better.[xi]

Finally, I need to briefly say a word about my personal conflicts and their outcome. The good Lord blessed me with a calm and accepting disposition which was nurtured by my mother’s piety and my father’s paternal affection. But Jesus also warned us (or was it a promise?) that he had come not to bring peace but the sword, “and one’s enemies will be those of his household” (Mt 10:35-36). This blessing, too, was not absent from my life.

When Father Germaine Blancal joined our community he was a sixty-one year old priest who had belonged to a religious congregation that was dedicated to the Sacred Heart. He was a renowned preacher who was much in demand, but his understanding of devotion to the Sacred Heart was very different than our own. Some who shared his views, and wanted him to lead our religious family, circulated uncharitable letters (for which they later sincerely apologized). This storm cloud passed, but try as I might I was unable to breach the wall between us. When I made a paternal visit to the house where he was superior, I found “intrigue, division, and a bad spirit” (NQT XII, 62). When a disagreement arose over a debt of 700 francs, I advised the treasurer to cancel it so that we might have peace. Then, when religious congregations were being expelled from France, Father Blancal was too ill to travel. I cared for him until he died — peacefully and without suffering. Subsequently, I eulogized him for all his priestly virtues of piety, charity, and simplicity: “Let us imitate him while praying for him” (LC I, 378).

At about the same time that the difficulties with Father Blancal broke out Bishop Thibaudier, who had always shown paternal solicitude to us and our works, was transferred to the diocese of Cambrai, and he was replaced by Bishop Jean-Baptiste Duval. Soon afterwards I wrote in my Diary: “Monsignor [Duval] is extremely distrustful. He twists and turns the sword in my wounded heart. Fiat, fiat!” (NQT IV, 104v). This continued through the summer: “Days of trial . . . Humiliation comes in a thousand disguises” (NQT V, 11v). He ordered me to live outside the diocese for three months of the year (I spent the time in Rome reading extensively about social problems and theories). “I did not have the temperament of a fighter. My nature led me to be good toward everyone and I wanted them to be the same toward me” (NHV XIII, 23). His attitude was often inconsistent: although he encouraged my social apostolates and advised troubled priests to seek my counsel, in matters concerning the Congregation and Saint Jean’s he was harsh and unyielding.[xii] Ultimately, early in the academic year of 1893, he ordered me to resign from the school. “A day of sacrifice. I am leaving Saint Jean’s where I have lived for sixteen years . . . I have a heavy heart and eyes full of tears . . . Temptations to discouragement assail me” (NQT VI, 40r).

In hindsight, I would be able to celebrate this turn of events as one of the greatest providential blessings in the history of the Congregation. Freed from the burden of the day-to-day oversight of the school, I was able to make the development and expansion of the Congregation my main priority. Over the next three decades it would go from being exclusively French to achieving a worldwide presence firmly established on five continents. The membership would increase from thirty-nine priests in July 1893 to almost four hundred priests among eight hundred professed members at the time of my death in August 1925.

I never understood what caused the animus that Bishop Duval felt towards me. I found it impossible to form any semblance of a personal relationship with him. Years later I came across a passage from one of Saint Augustine’s letters that gave me some insight: “A prince serves in one way because he is a man and he serves in another way because he is a ruler” (cf., NQT XXXVIII, 64). Bishop Duval assumed the mantle of a prince when he related to me, thus I was never able to develop a personal relationship with him. “For I too am a man subject to authority . . .” (Mt 8:9).

In the world today there is much greater awareness of importance and need for reconciliation, especially among ethnic groups, religious traditions, and social classes. This is a positive development that you should welcome and foster. But you should never forget that its source and its power is from God who was in Christ reconciling the world to himself, not holding our sins against us, but entrusting us with the ministry of reconciliation (cf., 2 Cor 5:19). As Saint Francis de Sales taught, “Our love for God” (I would add and for our neighbor) “is the distinctive and special effect of His love for us” (Love of God, Bk. III, Ch. 2). Since the beginnings of the Congregation this has been expressed in our daily Act of Reparation. When our Lord invites us to “Behold this Heart that has loved you so much,” we respond that “henceforth we shall strive to return love for love (redamare)” (OSP VII, 271).

Reconciliation is the gift of love for love.[xiii]

Jean du Coeur de Jésus

NOTES

[ii] City of God, XIX, 19.

[iii] Although many modern commentators refer to what Christ did for us and for our salvation as the “Christ-event” or the “work” of Christ, Paul never used either of these terms. “Christ-event: A shorthand expression for the redemptive actions of Jesus in history. As used by scholars, it typically includes the full sweep of his Incarnation and public ministry as well as his death, Resurrection, and Ascension.” Joseph Ratzinger. Jesus of Nazareth. Part Two. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2011, p. 312. For a fuller discussion of Christ’s “works,” cf., Fitzmyer, Joseph A., S.J., “Pauline Theology,” The New Jerome Biblical Commentary. Ed., Raymond E. Brown, S.S., Joseph Fitzmyer, S.J., Roland E. Murphy, O. Carm. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1990, 1397-1401. Cf. also, Fitzmyer, Joseph A., S.J., “Reconciliation in Pauline Theology.” in No Famine in the Land. Studies in honor of John L. McKenzie. Ed., James W. Flanagan and Anita Weisbrod Robinson. Missoula: MT: Scholars Press, 1975, pp. 155-157.

[iv] Cf., Dupont, Jacques. La Réconciliation dans la Théologie de Saint Paul. Bruges-Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 1953, p.5.

[v] In 4 Sent., d. 15, q. 1, a. 5, sol. 2, cited in Dictionnaire de Spiritualité 13, col. 236.

[vi] Cf., Dupont, Réconciliation, pp. 29-33,

[vii] “Paul sees justification as a step toward reconciliation . . . The third effect of justification is a share in the risen life of Christ, which is salvation. Although justification and reconciliation are things that happen now, salvation in the full sense is still to be achieved . . .” Fitzmyer, Joseph A., Romans. Anchor Bible. New York: Doubleday, 1992, p. 401; cf. also p. 394.

[viii] Cf., Glotin, Edouard. “Réparation,” Dictionnaire de Spiritualité. 13. Paris: Beauchesne, 1987, col. 370.

[ix] Cf., Adnès, Pierre, “Réconciliation,” Dictionnaire de Spiritualité. 13. Paris: Beauchesne, 1987, col. 236.

[x] “A twofold dimension — horizontal and vertical — is at work in the reconciliation of human beings. It is ‘horizontal’ reconciliation if it encompasses the reunion that it brings about ‘in the unity of the children of God’ and the mutual relations that such a reunion implies and supposes. It is a ‘vertical’ reconciliation if it reassembles all humanity at the foot of the cross and, by and in Jesus, brings about the reconciliation with the Father. This is the twofold dimension of reconciliation to which John Paul II directed our attention in his Exhortation Reconciliatio et Paenitentia (n. 7) . . .

“This should be acknowledged as a true dialectic of reconciliation. The same dialectic that we can recognize between the love of God and the love of neighbor . . . It is through and in our mutual love that our love for God is made manifest.

“It is in this way that the twofold dimension of reconciliation is achieved by and in Christ: (horizontal) reconciliation of people among themselves through their (vertical) reconciliation with God; but it is because in him and through him, Christ gathers them together and (horizontally) reconciles them between themselves in the unity of his Body that they are, in him and through him, (vertically) reconciled with God.” Bourgeois, Albert: Notre Règle de Vie: Un Itinéraire. Studia Dehoniana 15.3. Rome: Centre Général d’Études (1989), p. 709.

[xi] Cf., Haughton, Rosemary. The Catholic Thing. Springfield, IL: Templegate Publishers, 1979, p. 17.

[xii] Cf., Manzoni, Leo Dehon and his Mission, pp. 322-23.

[xiii] “. . . the work of reconciliation, like the work of redemption, appears most clearly as a work of reparation . . . it is all throughout the text of the Constitutions that the idea of ‘reconciliation’ is identified and explained as what we are called to understand and live as ‘reparation’ . . .

Since 2 Cor 5:18-21 sums up the entire redemptive work of Christ as the work of reconciliation, it is in the service of reconciliation that our ‘reparation’ is understood and lived ‘as a response to Christ’s love for us and a communion in his love for the Father,’ in and through the ‘cooperation in his work of redemption in the midst of the world’ [cf., Cst. n. 23].” Bourgeois, STD 15.3, pp. 772, 774.

Cf., also Lyonnet, Stanislas, “A Conference on Reparation,” Studia Dehonianna 7. Rome: Centro Generale Degli Studi, Sacerdoti del S. Cuore, 1973, p. 28: “‘reparation’ is an approximate synonym for redemption, reconciliation, and restoring order.”