“Do something that I cannot: Vote! Become informed. Have conversations with others. Write and call your representatives. Don’t be silent, don’t assume that you can’t make a difference. Everyone can make a difference.”

-Cendi Trujillo Tena

The fate of DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) has been in the headlines since September when President Donald Trump announced plans to rescind it. Created in 2012, DACA is a federal program that allows people brought to the United States without documentation as children the temporary right to live, study and work in the US. After undergoing a rigorous vetting process, those who receive two-year DACA status can become eligible for things that many US citizens take for granted such as a work permit, college enrollment (but not government aid) and a driver’s license. Approximately 788,000 people have such status.

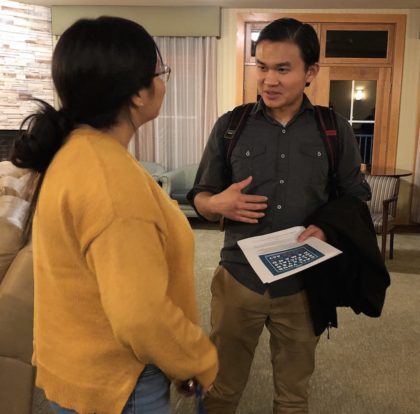

One of those with DACA status is Cendi Trujillo Tena. She shared her story with SCJs (Dehonians) during an informal gathering at Sacred Heart at Monastery Lake last night (November 28).

Posing as the child of a US citizen (a smuggler paid by her parents to accompany her), she crossed the US-Mexican border when she was two years old.

Cendi said that it was an easier route than what many others have taken. “One of the kids I work with watched four people die in the back of a van as they were smuggled toward the border,” she said.

A youth organizer at Voces de la Frontera, a migrant advocacy organization in Milwaukee, Cendi has heard numerous such stories. But the challenge of crossing the border is just one of many that the undocumented face. Often fleeing violence and extreme poverty, parents make the difficult decision to move their family to the United States without papers in hopes that their children will have opportunities not possible in their home country.

Of course, at the age of two Cendi had no idea that she was doing something considered illegal, and that once in the country, that she would have limitations which many of her classmates did not.

It wasn’t until she was a pre-teen that she came to understand what being undocumented meant. She wanted to get a job to help pay for her school supplies and learned that she would need a fake Social Security number to do so.

She went to work at 14 and set her sights on college. “I had been on the honor roll since kindergarten,” said Cendi.

But as an undocumented person, she soon learned that she wouldn’t qualify for grants or loans.

“My mother told me that if I worked hard God would help me,” said Cendi. “But without a Social Security number, working hard wasn’t good enough.”

A teacher offered to adopt her to help her qualify for aid. “It was kind, but not possible,” she said. “I have parents and my parents are here.”

Once she had DACA status, she had more possibilities. It didn’t make her eligible for student aid, but she could work legally and get a driver’s license. Best of all, “I didn’t have to look over my shoulder all the time.”

Cendi, like many “Dreamers,” as those protected by DACA are called, pays taxes, but she is still not eligible for any government benefits. “We own houses, we serve in the military, we are a part of the community but we still have no real status. DACA is not a path toward citizenship.”

Every two years the Dreamers have to pay $495 to reapply for DACA status. On top of that, many people pay hefty legal fees –– sometimes to scammers –– to help them sort through the paperwork. “It is money that most undocumented people cannot easily afford,” she said.

If DACA is repealed, even this legal “non-status” may no longer be an option, leaving many Dreamers to wonder “What next?”

“What about following the law and applying for citizenship legally?” asked one SCJ, echoing a question that he hears many ask. “Others wait in line and follow the rules to gain citizenship; why is the situation of these people different? Why should they be outside of the law?”

These are questions asked by many trying to get a sense of immigration policies.

“Laws change,” said Cendi. “At one point the law said that slavery was legal in the United States. But it was morally wrong and the law was eventually changed.”

For most undocumented there is no practical, legal path to US citizenship. The application process timeline can take years, leaving applicants in a non-status limbo while both following the law and hiding from it.

“For me right now there are only three real options for permanent residency,” said Cendi. “I could get married –– and that isn’t a sure thing. I could be a victim of a serious crime. Or I could cooperate with the government about a significant crime that someone else committed.”

With so many challenges to living as an undocumented person in the United States, often with no hope for legal status, “Why did your family come to the country?” asked an SCJ.

“My father had a second grade education,” began Cendi. “He had 13 brothers and sisters and stole food from the corner grocery to help feed them. The oldest siblings are smaller than the younger ones because of malnutrition. But it isn’t an easy decision to come here.”

“I have mixed feelings about the word ‘Dreamers,’” she continued. “It makes children seem like victims of the actions of irresponsible parents. But the parents are the original dreamers. They sacrificed so that we could be here.”

Some have suggested that DACA be continued but with the caveat that more money be put into border security, including a wall between the US and Mexico.

“But we do not want to be bargaining chips tied to other legislation,” said Cendi. She and fellow Dreamers aren’t concerned only for themselves. They are concerned about their families, and others like them who continue to seek legal ways to leave areas of extreme violence and poverty.

Cendi advocates for more than just a continuance of DACA, but for the implementation of the “Clean DREAM Act,” known formally as the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act. The bill’s aim is to give undocumented young adults a path to citizenship. A version of the legislation was first introduced in 2001 but has yet to be passed. DACA was considered a temporary fix while the bill was debated.

What can people do? What can Dehonians do?

“You helped us to realize that as Dehonians we are called to know the people on the street, to know people where they are, especially to be aware of the suffering migrants in our area and around the world,” said Fr. Richard MacDonald, SCJ.

“The most important thing is to be involved,” added Cendi. “Do something that I cannot: Vote! Become informed. Have conversations with others. Write and call your representatives. Don’t be silent, don’t assume that you can’t make a difference.

“Everyone can make a difference.”