Industrial Revolution set the stage for founder’s early ministry

“Clergy have to learn about economic issues and the problems of social science… Our seminaries have to offer courses in social and political economics.”

Who said it? Originally, Fr. Leo John Dehon, founder of the Priests of the Sacred Heart.

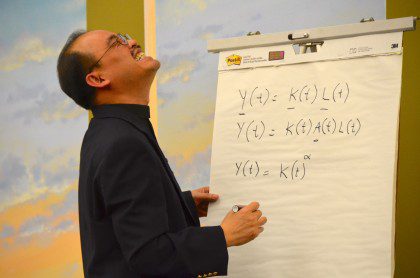

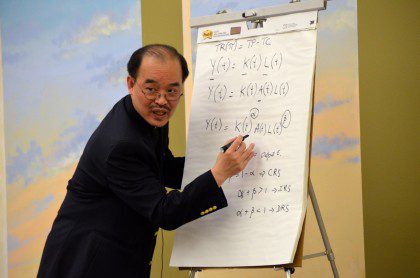

Echoing it about a 100 years later was Fr. Quang Nguyen, SCJ, presenter at Sacred Heart School of Theology’s annual Dehon Lecture on March 26. The title of his presentation: “Fr. Dehon’s Ministry from an Economic Perspective.”

Fr. Quang began by listing the founder’s academic resumé, including degrees in canon and civil law, theology and philosophy.

“But was he an economist?” asked Fr. Quang. Fr. Dehon held no degree in the field, but “his self-taught knowledge and respect for the discipline of economics was evident in his ministries and in his young congregation.

“His approach to ministry signified a deep understanding of economic issues and principles. And he did not stop at understanding the issues and theories but more important, he put them into practice.”

“Christ exerts His influence through His Church,” Fr. Dehon wrote. Economics is one of the driving forces of society. If priests and religious are to influence society, they must be educated in what drives it. How are the people of a society affected by economics?

How can economics be affected by the people of a society?

Fr. Dehon began his priestly ministry in the midst of the Industrial Revolution in France. It was in the gritty factory town of Saint Quentin that the roots of the Priests of the Sacred Heart took hold.

“The relationship between industry and labor resulted not only in the mass production of goods for consumers and industry, but also in massive fortunes for the wealthy ownership class and economic deprivation for the working class,” said Fr. Quang.

Employees as young as six worked 12-hour days, and sometimes longer. Family structures were strained. People were treated as expendable cogs in the factory machines.

Fr. Dehon, by birth a member of France’s aristocratic elite, courageously challenged these social injustices. “An example of his courage was his Christmas Sermon in 1871 where he denounced ‘the deplorable organization of the world of business and labor,’” said Fr. Quang. “He saw a situation in which working men and women were no longer able to obtain the minimal requirements that were essential for human survival.”

Essential in Fr. Dehon’s efforts to improve the lives of workers, said Fr. Quang, was that the founder didn’t demonize one side of the equation over the other. He didn’t just rally on the side of the worker without considering the concerns of the business owner.

“There are two main approaches in economics,” said Fr. Quang. “Traditionally you either maximize profit or minimize loss… Employers either have to increase prices in a market which is fairly competitive or reduce the cost which would include the wages and benefits of the workers.”

The business of business is to make money. But when financial profit is the ultimate goal, “the well-being of the employer ends up being held in higher regard than that of the worker,” said Fr. Quang.

Fr. Dehon challenged this. “He provided workers with information that would legally and morally help them to improve their wages and working conditions,” said Fr. Quang. “By organizing unions he helped them to have a collective voice that could not be ignored by owners.

“But most importantly, through his care and assistance, Fr. Dehon enabled workers to reclaim the endowed human dignity that had been neglected and trampled upon.”

He did this “not by creating a war between workers and factory owners, not by entering into a ‘blame game’ or calling for a redistributive economy,” said Fr. Quang. “Instead, he tried to serve as a bridge connecting the two sides, as an instrument for closing the inequality gap.

Pitting workers against their employers could have easily backfired. In an economy where there was a surplus of labor, business owners could have set even more challenging working conditions, assuming that there were always people desperate enough to take them. Employers could have moved their factories, or fired “troublesome” workers who challenged the status quo.

“Worse yet, such situations can become violent when employers and workers are unable to find a common voice to address their differences,” said Fr. Quang.

“Fr. Dehon recognized that it was important to evangelize the workers but even more necessary to instill into the employers the living of the Gospel… after all, employers held the greater responsibility and had the means to make a difference.”

Fr. Quang noted that Pope Francis, in the opening Mass of his pontificate, said much the same:

““Please, I would like to ask all those who have positions of responsibility in economic, political and social life, and all men and women of goodwill: let us be ‘protectors’ of creation; protectors of God’s plan inscribed in nature, protectors of one another and of the environment.”

Like Pope Francis, Fr. Dehon not only helped workers to organize so that their voices could be heard, “but he also appealed for the participation of people from the other side of the equation, those who had the power and ability to make a difference in the lives of those entrusted to their care, despite the fact that this would not easy to do,” said Fr. Quang.

“The apostolate among management is often ineffective,” Fr. Dehon is said to have complained.

“But setbacks did not dissuade him from moving forward,” said Fr. Quang. “Using his own recognition and family influence, he approached leading employers and made them aware of their responsibilities. Surprisingly, some of the employers eventually became his friends and active collaborators in his ministry.”

Fr. Quang continued, noting that Fr. Dehon sought systemic, long-term solutions. He wasn’t just trying to make the lives of workers of his day better, but the lives of the next generation as well. He did this by emphasizing education.

“Without education he recognized that the children of workers were likely to face the same dilemma as their parents,” said Fr. Quang. He invested in youth, increasing the value of their “human capital” by creating educational opportunities, such as St. John High School.

“Those who invest in education are predicted to have higher income levels than those who don’t,” said Fr. Quang. “This was Fr. Dehon’s long-term goal for the people of Saint Quentin.”

Fr. Quang challenged his audience –– many of whom are seminarians at Sacred Heart School of Theology –– to look at how they can affect change in today’s world.

“I think that today’s globalization can be seen as another Industrial Revolution,” said Fr. Quang. “There are many of the same characteristics, similar challenges.

“Can we –– as Fr. Dehon did –– do anything to affect change?

A panel discussion followed the presentation, helping participants process what they had heard. Panelists included seminarians who had experience in the business world, whose experiences put them on both sides of the business equation. Their lived realities showed the many grey areas in the questions; there are not easy black and white answers to the concerns brought forth by an increasingly disparate economy.

“We need to ‘evangelize’ in a sense; working together to help employers and shareholders realize that the bottom line is not always the bottom line,” said one of the panelists. “We can help to open up conversations, to get various sides to understand one another, to help humanize the business equation.”

“We all have responsibility,” said an audience member. “Many of us own stocks, if not directly, then through retirement plans or mutual funds. Do we make the effort to find out what is being done in our name? We are business owners too.”

“The economy is global,” said another. “But so too is our faith.”

Fr. Quang Nguyen received his Ph.D. in Economics/Political Science from Claremont Graduate University in California last year. He professed his first vows with the Priests of the Sacred Heart in 1995.